Mathematics and beauty

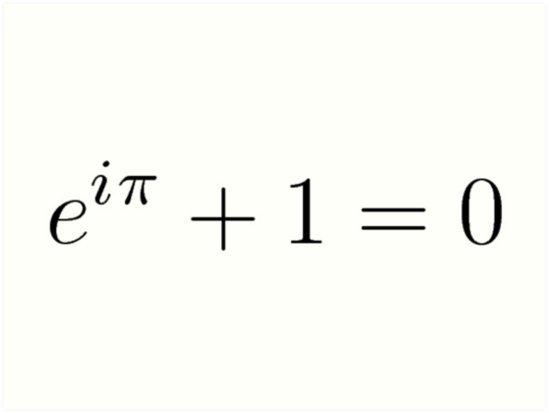

Modern mathematics is one of the most enduring edifices created by humankind, a magnificent form of art and science that all too few have the opportunity of appreciating. The great British mathematician G.H. Hardy wrote, “Beauty is the first test; there is no permanent place in the world for ugly mathematics.” Mathematician-philosopher Bertrand Russell added: “Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty — a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture, without appeal to any part of our weaker nature, without the gorgeous trappings of painting or music, yet sublimely pure, and capable of a stern perfection such as only the greatest art can show.”

Yet it is a sad fact that few people on this planet even begin to grasp the full power and beauty of mathematics. For the vast majority of humankind, even in first-world nations, all students see of mathematics is some relatively dull drilling in decimal arithmetic (e.g., the dreaded times tables), some very basic algebra and various textbook “story problems.” Most never glimpse the higher-level beauty of real modern mathematics that lies at the end of the tunnel. Many otherwise promising students lose interest in mathematics as a result of dreary instruction, often by teachers who did not major in mathematics and for whom teaching mathematics is a chore. Inevitably, math homework often loses out to social media, computer games, parties and sports. The result is a tragic waste of desperately needed mathematical talent for the present and future information age.

The elegant theorems and proofs of mathematics

Part of the problem here is that hardly any students ever see some of the more beautiful parts of mathematics, such as elegant proofs of important mathematical theorems. Some of these theorems may be mentioned in textbooks, but often their proofs are dismissed as “beyond the scope of this text,” relegated to some higher-level mathematics course only taken by advanced math majors or graduate students, which is an extremely tiny audience. Even when these proofs are part of the curriculum, the presentation in textbooks often fails to highlight the keys ideas in a way that students can easily grasp and gain intuition.

As a single example, the fundamental theorem of algebra, namely the fact that every algebraic equation of degree n has n roots, typically is presented in a college-level course in complex analysis, and then only after an extensive background of underlying theory such as Cauchy’s theorem, the argument principle and Liouville’s theorem. Only a tiny percentage of college students ever take such coursework, and even many of those who do take such coursework never really grasp the essential idea behind the fundamental theorem of algebra, because of the way it is typically presented in textbooks (this was certainly the editor’s initial experience with the fundamental theorem of algebra). All this is generally accepted as an unpleasant but unavoidable feature of mathematical pedagogy.

A new blog feature: Simple proofs of great theorems

The editor of this blog rejects this defeatism. He is convinced that many of the greatest theorems of mathematics can be proved significantly more simply, and requiring significantly less background, than they are typically presented in traditional textbooks and courses.

Thus the editor has decided to start a new feature in this blog, namely to present simple, beautiful and readily understandable proofs of a number of important theorems. In most cases, as we will see, this can be done without sacrificing rigor, and yet also without a huge background of prior coursework and machinery that many younger students especially might not have the patience or time for.

The proofs envisioned for presentation will be designed to satisfy the following requirements:

- The proofs will include some historical background and context.

- In most cases, the most simple, elegant and beautiful proof of a given theorem will be the one presented.

- Whenever possible, the proofs will be suitable for presentation to bright high school students or, at most, first- or second-year college mathematics students.

- Any necessary lemmas or other background material beyond very basic facts will be included.

- The entire proof, including historical context and background material, will not exceed three pages or so.

An impossible dream? The editor is convinced otherwise.

Current “simple proof” articles:

Here are the articles currently in the series. Others will be added in the future:

- The irrationality of pi

- The fundamental theorem of algebra

- The impossibility of trisection

- The fundamental theorem of calculus

- Archimedes’ calculation of pi

- Pi as the limit of n-sided circumscribed and inscribed polygons

Comments and suggestions are welcome

Comments on any of this material certainly welcome. What’s more, if a reader has a suggestion for some theorem that not yet been featured, or even for an alternate proof of some theorem that already has been featured, please contact the editor. His email is given at Welcome to the Math Scholar blog.